I attended Black Hat 2011 and DEF CON 19 this last week under the auspices of Mozilla. We generally have a bunch of us who are involved in facets of the security releases attending these back to back conferences every Summer in Las Vegas. This is for a few reasons but the primary ones are to be on hand for the exposure of potential zero day security holes in Firefox and to get a sense of the direction and focus of the work going on in exploiting browsers (and security in general).

Some years, there is a lot of browser specific exploits being done. This year, this seemed to not really be the case with people either focusing a lot on overall system/infrastructure issues (DNS, SSL as a whole) or on opportunities in the growing mobile space (and including Chrome OS as well).

Some of the take aways I have, at a fairly high level, are that mobile is becoming more and more important. A couple of years ago, mobile was seemingly very important. Looking back, that seems almost quaint given how smartphones, iOS, and Android have grown in the last few years, making the intersection of the Internet and phones simply an ubiquitous part of life. Over time, I notice a lot fewer laptops being carried about and a lot more in the way of tablets and high end phones. That just kind of points to the direction of things. I noted that I saw three or four penetration testing suites in booths at Black Hat that were based on using Android as a penetration testing platform. While it has been possible for a while, I don’t recall there being that many explicitly commercialized offerings in previous years.

The Arab Spring and its implications were also readily evident. I gather from Bruce Sutherland’s comments the DEF CON, at least, actively solicited presentations relating to it. I’ll highlight a few talks below that directly referenced it but there was a lot of thinking going on about Internet, communication in crises or when governments cut off access, and the clear importance of worldwide communication in troubled situations.

On to talks!

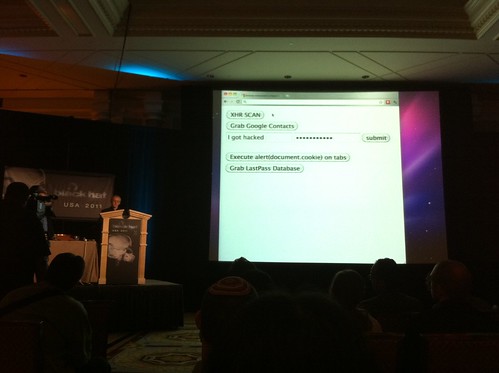

At Black Hat, among other talks, I attended Matt Johansen’s and Kyle Osborn’s talk, “Hacking Google Chrome OS.” This talk focused on Chrome OS as present on the recently offered Chromebooks. Matt and Kyle have been playing with things there for most of the last year and found a number of exploits (the ones demonstrated were reported and fixed). As they point out, issues around cross-site scripting become even more important when the browser they occur in is actually the basis of your entire operating system and user experience. They also showed that, contrary to the impression that many people have, Google does no real validation on the addons uploaded for Chrome. People can write arbitrarily exploitive addons for Chrome and have them immediately available to users of Chrome on Google’s own site. Google also has, until just the last few weeks, had almost no guidelines on how to write a secure addon or best practices. By doing standard web browser attacks on an addon being run as if it were a separate program in Chrome OS, they demonstrated cookie stealing, clickjacking, and even theft of personal data (the contact list and its contents) as being very possible.

This was a lot of fun and it is good to see people digging in here. None of the basic ideas or attacks were novel (nor were they required to be so). This just really illustrated the dangers of extending the browser extension and trust models to entire operating systems. I would bet that many of the same sorts of things would work on WebOS and possibly on at least HTML5 apps on iOS.

Given Google’s integration of services, these attacks also exploited access to Gmail and Google Voice, for example. With so many essential services tied together, there is real potential exposure.

Another talk that I really enjoyed as Moxie Marlinspike’s “SSL And The Future Of Authenticity.” I’ve heard Moxie speak a few times and am acquainted with him and he’s always an engaging and thoughtful speaker (and a few monotone-like talks that I attended really reinforced that).

Moxie spoke, as he often does, on the problems with SSL. He went over the exposure of Comodo earlier this year and the ongoing problems there are with root certificate authorities really not doing a very good job at both vetting people and applications and at protecting their data. A fundamental issue is that many of the root CA’s are, essentially, “too big to fail.” Given the huge portion of the SSL certificates that come through a few key players, even when they screw up, the option of removing their trust from web browsers is not really available to browser vendors. All of the browser vendors (or most of them) would have to agree in order to do that or users would simply see, say, 15% of the SSL on the net no longer working as a browser bug. Even if everyone agreed, can we really afford to have that much of the SSL net become unavailable? Basically, we are much too centralized with a huge legacy problem (and I happen to very much agree with this).

Moxie proposes a solution, which is the decentralization of authority from the current certificate authority system. Rather than trusting a monolithic set of CA’s, Moxie proposes “notaries” that are user designated and who provide their own validation of sites. Users configure themselves to use (ideally) a set of notaries, whom they trust, that each return data concerning a site when requested. By looking at the aggregate of returned data from the notaries, users can have the browser make decisions on whether to trust a site. He’s put up a beta technology for this end called, “Convergence.” This currently runs using a Firefox extension as a reference implementation. You can see the details as outline by Moxie here. Code is also available for groups or individuals to set up their own notaries.

I haven’t thought through how well this kind of system would work in practice with billions of potential users but Moxie is a smart guy (smarter than me) and he’s put a lot of thought into it. It is definitely worth investigating. To me, it seems very clear that the current, legacy, CA system is pretty broken and no one has a real means to fix it. Moxie’s ideas propose at least one alternative.

Alessandro Acquisti of Carnegie Mellon University did a talk on images and Facebook called, “Faces Of Facebook-Or, How The Largest Real ID Database In The World Came To Be.” This looked at the meeting of facial recognition technology and the rampant self-disclosure, via photos, that happens on Facebook (though it also happens via Flickr and other services as well) in combination with real names (Hello, Google Plus!) and other sensitive data. As a research project at CMU, Acquisti and his team used some standard image recognition software, Pittsburgh Pattern Recognition (PittPatt) developed at CMU, and applied it against public photos on Facebook and some dating sites. They pulled over 275,000 publicly available profile images of Facebook members in a particular city in addition to photos from other sites, Acquisiti mentioned. They were able, for discrete groups or locales (such as a university or a city) identify at least a third of supposedly anonymous students in the study from their photos and those of their friends. From this, they were able to often get date of birth, social security numbers, and other data (27% of the time after four attempts). Acquisti said,

“In all, about 5,800 dating site members also had Facebook profiles. Of these, more than 4,900 were uniquely identified. The numbers are significant because a previous CMU survey showed that about 90% of Facebook members use their real name on their profiles. Though the dating site members had used assumed names to remain anonymous, their real identities were revealed just by matching them with their Facebook profiles.”

They were able to identify people hidden in the public photos of other Facebook users based on their existing identification with facial recognition. This could be used to show networks of associates and possibly to help build a social graph for these people.

When we think of ourselves as being anonymous with our friends or at events, this kind of work shows that we really aren’t. This is all the more true since these photos aren’t going away (I have photos online from the 1990′s) and the techniques can always be applied retroactively to older data if it is captured.

Acquisti makes the point that we should probably just not consider ourselves anonymous online if we engage in social networking and expose photos. This could obviously be extended to other kinds of data as well. Our data footprints are large and only getting larger through continual use of services like Twitter, Facebook, Google Plus, and whatever becomes the next big thing a few years from now. Someone is going to be able to connect the dots between your online presence and your life unless you, essentially, do not use the full features of many of these services.

These were at Black Hat. At DEF CON, there were a couple of presentations about getting your data out in an emergency or when communication has been shut down by the government:

- Staying Connect during a Revolution or Disaster by Thomas Wilhelm

- Dust: Your Feed Belongs to You by Chema Alonso and Jun Garrido

- How To Get Your Message Out When Your Government Turns Off the Internet by Bruce Sutherland

Thomas Wilhelm’s presentation focused on setting up mesh networks with smartphones in an emergency or political situation. He calls it “Auto-BAHN” and has an alpha Android application up at hackerdemia.com. His focus is on using point to point communications to communicate dynamically without a centralized infrastructure so that when cell towers go down (and his examples are in both Katrina and Egypt type situations), people can still get the word out amongst themselves and also, potentially, communicate with authorities as they become available. Wilhelm would like to see this kind of communication built in by mobile operating system manufacturers and/or cellular providers because of the implications for disaster responsiveness, when our phone mostly become power hungry bricks.

The idea behind Alonso and Garrido’s Dust presentation is to make the feed of your sites available from multiple sources, instead of one canonical and centralized source. That way if it becomes unavailable (or is taken down) there are mechanisms to still get information out. I think that they are largely looking at a Wikileaks style scenario. They want to use a peer to peer backend as a secondary feed source. They haven’t published any other information yet though Alonso did demonstrate a proof of concept during the talk.

Sutherland’s presentation focused on Ham radio, specifically the use of packet radio and satellite’s to get data out of crisis zones without going through normal infrastructure. He wants to use APRS, a digital ham radio protocol, to send e-mail and, more specifically, to talk directly to twitter. Given the role of twitter in recent uprisings and unrest, he sees it as an essential service for people to communicate with both each other and the world. His APRS to Twitter gateway is up at www.hamradiotweets.com, which will post messages under @hamradiotweets on twitter. His presentation is actually available as a PDF if you’re interested in reading it.

The most amazingly out of the box and geeky talk I attended was the “Sounds Like Botnet” presentation by Itzik Kotler and Iftach Ian Amit. This was a proof of concept talk and demonstration of setting up a botnet command and control system using voice over IP (VOIP) systems. As Kotler and Amit pointed out, even on supposadely closed networks, people are often allowed (or even required) to run VOIP software in lieu of having actual phones. Because it needs to communicate with the real world (or else it isn’t much of a phone system), these systems often directly bypass firewalls and other protections. Additionally, because they haven’t traditionally been considered an attack vector, the VOIP systems are often pretty much ignored and unmonitored by the IT security apparatus at companies.

Their proof of concept implementation is moshimoshi, which is a Python script that can connect using SIP to a SIP server, such as Asterisk. They demonstrated it working with one laptop running the bot and then calling into a conference room (where many bots could call in) on an Asterisk server and then telling the bot to do things using DTMF tones. They also had the bot use both text to speech, to read a file aloud, and also transmitted data in the audible range using 16 tones to encode it (which sounded almost musical). They pointed out that if you wanted to be more advanced, you could use the old modem protocols on top of VOIP and then run TCP/IP on top of that. It strikes me as being pretty slow but it would undoubtedly work to transmit data back and forth easily.

You can view the presentation as a PDF or via Slideshare.

I attended many many other talks but these were the ones that I thought would be interesting to mention here. For DEF CON, at least, the videos of this year’s talks will probably be available to the public sometime next Spring (this often seems to be the case though I haven’t tracked it closely). Video sets were being sold at both conferences and are probably still available, though prohibitively expensive for most people.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

.